Download

Word '97 file now (In Win Zip Format: File Report.zip)

Download Powerpoint

Presentation now (In Win Zip Format: File Present.zip)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 ANALYSIS OF INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORT INDUSTRY

1.1 INTRODUCTION

1.2 LOCATION OF SOFTWARE COMPANIES

1.3 DOMESTIC SOFTWARE INDUSTRY

1.4 SOFTWARE EXPORT INDUSTRY

1.5 STRUCTURE OF SOFTWARE EXPORTS

1.6 DESTINATION OF INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS

1.7 DEVELOPMENT FOCUS OF THE SOFTWARE EXPORTERS

1.8 MARKETING CHANNELS USED BY SOFTWARE COMPANIES

1.9 SEGMENTS OF APPLICATION SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT

1.10 DEVELOPMENT PLATFORM

1.11 TOP TWENTY SOFTWARE EXPORTERS

2 CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS

2.1 UNEVEN OUTPUT: SERVICES NOT PACKAGES

2.2 UNEVEN EXPORT DESTINATION: US DOMINATION

2.3 UNEVEN DIVISIONS OF LABOUR: 'BODY SHOPPING PRISON'

2.3.1 Uneven Locational Divisions: Onsite and Offshore Work

2.3.2 Uneven Skill Divisions: Dominance of Programming

2.3.3 Persistence of Onsite Programming Services

2.4 UNEVEN MARKET SHARE: ECONOMIC CONCENTRATION OF PRODUCTION

2.5 UNEVEN SITING: LOCATIONAL CONCENTRATION OF PRODUCTION

3 ANALYSIS OF OTHER SOFTWARE EXPORTING COUNTRIES:

3.1 AUSTRALIA

3.1.1 Effect of East Asian Crisis in Software exports of Australia

3.1.2 Implications for India

3.2 IRELAND

3.2.1 Focus on Exports

3.2.2 People with skills

3.2.3 Focus for Investment

3.2.4 Technology in place

3.3 FINLAND

4 INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS - EVOLUTION & STATE POLICIES

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 A BRIEF HISTORY IN TIME - SOFTWARE POLICY PRIOR TO 1984

4.3 1984-1990: GUIDED AND GUARDED LIBERALISATION

4.4 INDUSTRY EVALUATION OF SOFTWARE POLICY IN 1990

4.4.1 Appropriateness of policy's objectives

4.4.2 Altering the composition of Software Exports

4.4.3 Nature of liberalisation, government support or other policy

changes required

4.5 ECONOMIC LIBERALISATION - 1991 - 1998

4.6 PM'S IT TASK FORCE - THE NEW IT POLICY OF THE GOVERNMENT

4.6.1 Info Infrastructure drive

4.6.2 Target ITEX-50

4.6.3 IT for all by 2008

4.6.4 Data Security Systems and Cyber Laws

4.7 CONCLUSIONS

5 CONCLUSIONS

6 REFERENCES

TABLE OF TABLES AND FIGURES

TABLE 1.1: GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION OF INDIAN SOFTWARE COMPANIES 6

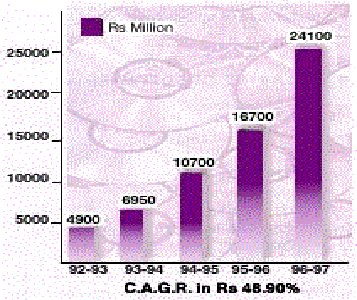

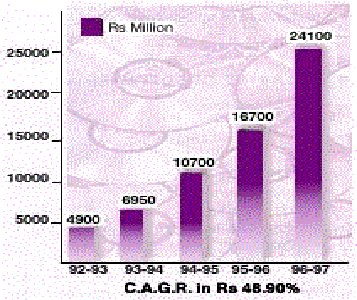

FIGURE 1.1: GROWTH OF THE DOMESTIC SOFTWARE INDUSTRY 6

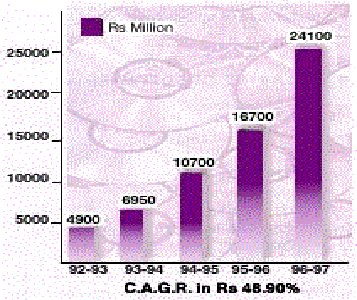

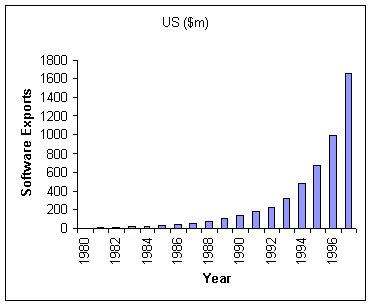

FIGURE 1.2: GROWTH OF SOFTWARE EXPORTS FROM INDIA 7

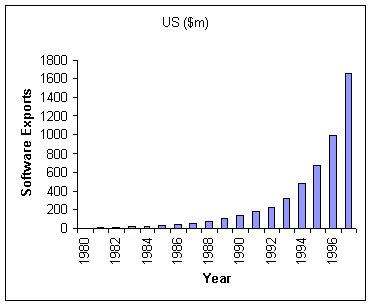

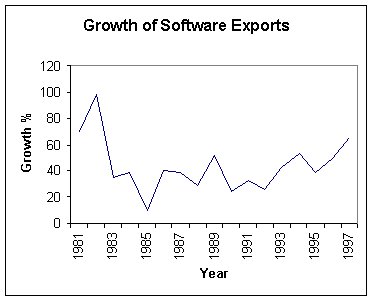

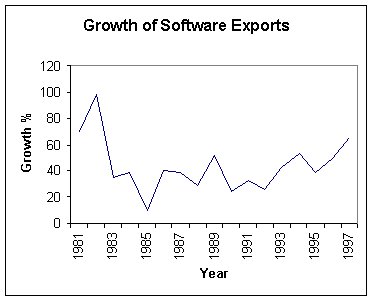

FIGURE 1.3: PERCENTAGE GROWTH OF SOFTWARE EXPORTS FROM INDIA 8

TABLE 1.2: STRUCTURE OF SOFTWARE EXPORTS 9

TABLE 1.3: BREAK UP OF THE SOFTWARE ACTIVITY 9

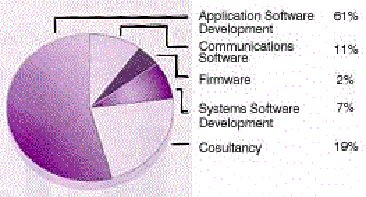

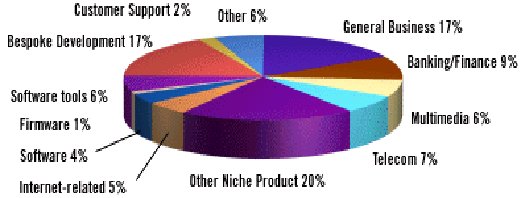

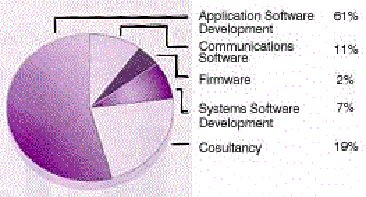

FIGURE 1.4: DEVELOPMENT FOCUS OF INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS 10

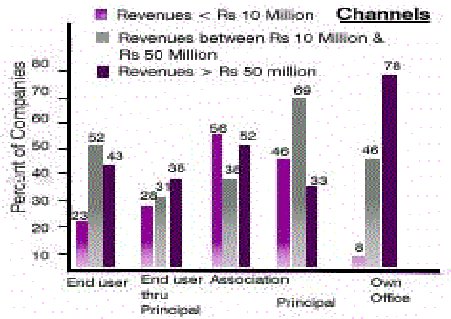

FIGURE 1.5: A BREAK-UP OF THE MARKETING CHANNELS USED BY INDIAN SOFTWARE

COMPANIES 11

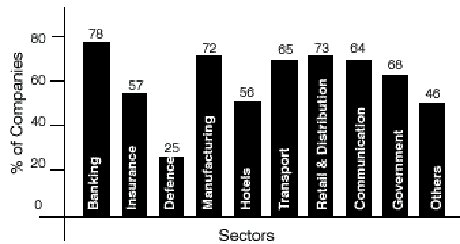

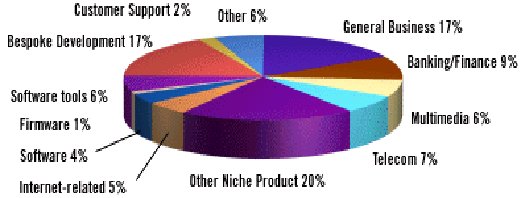

FIGURE 1.6: A BREAK-UP OF THE REVENUES BY SECTOR 12

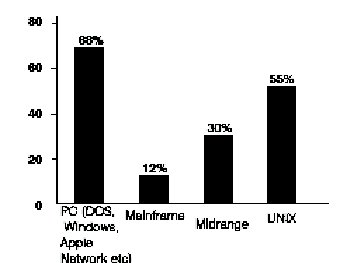

FIGURE 1.7: A BREAK-UP OF THE DEVELOPMENT PLATFORMS USED 12

TABLE 1.4: TOP 20 INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTERS 13

FIGURE 2.1: DESTINATION OF INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS 16

TABLE 2.1: LOCATION OF INDIAN SOFTWARE COMPANY HEADQUARTERS 20

TABLE 3.1: THE OTHER TOP EXPORTING ORGANISATIONS IN AUSTRALIA 21

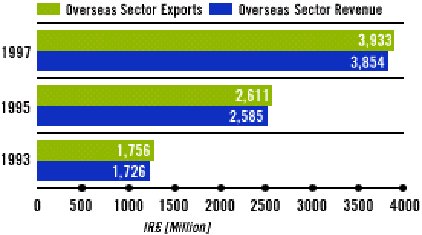

FIGURE 3.1: A PROFILE OF SOFTWARE EXPORTS OF IRELAND 22

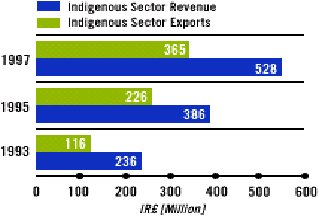

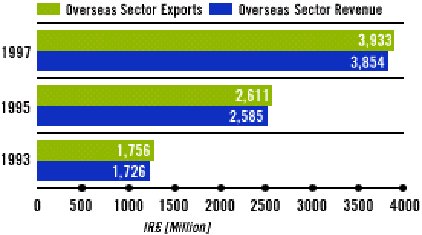

FIGURE 3.2: A PROFILE OF IRISH SOFTWARE EXPORTS 23

FIGURE 3.3: A COMPARISON OF IRISH EXPORT AND INDIGENOUS SOFTWARE INDUSTRY

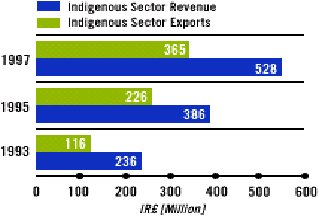

24

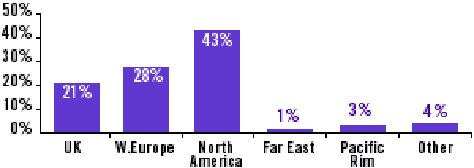

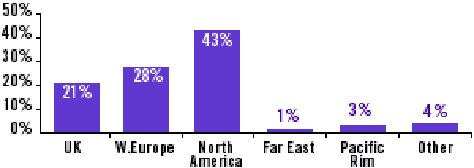

FIGURE 3.4: DESTINATION OF IRISH SOFTWARE EXPORTS 24

TABLE 3.2: REVENUES OF IRISH SOFTWARE INDUSTRY 24

TABLE 3.3: EXPORTS (AS A % OF TOTAL REVENUE) 25

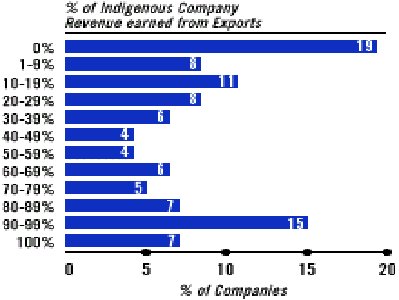

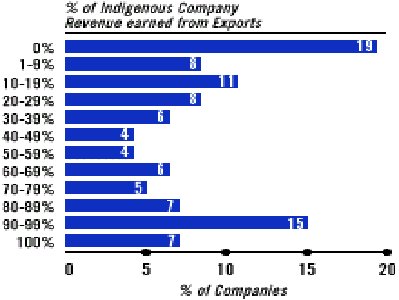

FIGURE 3.5: COMPOSITION OF IRISH IT INDUSTRY: 25

1 ANALYSIS OF INDIAN SOFTWARE

EXPORT INDUSTRY

1.1 Introduction

Currently, the software industry in India is worth Rs. 63.1 billion (US

$ 1.75 billion). If we add in-house development of the large commercial/corporate

end-users, then the total software industry is close to Rs. 80 billion

or US $ 2.2 billion, whereas ten years back the software industry in India

was not more than Rs.300 million or US $10 million.

The Indian software industry has a unique distinction in that most of

its output is exported. Of the turnover worth US $2 billion, over 50 per

cent is accounted by exports. The CAGR (Compounded Annual Growth Rate)

for the Indian software industry in the last five years has been 52.6%.

CAGR for the software export industry has been 55.04% while that for the

domestic industry has been 48.9%.

Despite these high growth rates, India's share in the world software

market is very low, but India still enjoys an advantage over some of the

other nations, which are trying to promote software exports. This is due

to the fact that India possesses the world's second largest pool of scientific

manpower which is also English speaking. Coupled with the fact that the

quality of Indian software is good and manpower cost is relatively low,

it provides India a very good opportunity in the world market.

1.2 Location of software companies

The industry is mainly concentrated around Metros. Lately, Hyderabad, Chennai,

Pune and Gurgaon have emerged as fast growing Software cities. At the same

time Bangalore and Mumbai continue to attract investment in software sector.

An analysis of the headquarters of the top 430 software companies demonstrated

the following statistics.

City

|

No. of Companies

|

|

Mumbai

|

115

|

|

Bangalore

|

87

|

|

Delhi, Gurgaon & Noida

|

70

|

|

Hyderabad

|

37

|

|

Chennai

|

51

|

|

Calcutta

|

25

|

|

Pune

|

23

|

|

Others

|

22

|

Table 1.1: Geographic location of Indian Software Companies

1.3 Domestic Software Industry

For years, no reliable date has been available on the Indian domestic software

industry. This is more so because the percentage of in-house development

of software is very high and it is difficult to accurately estimate its

value, in1996-97. The domestic software industry has been estimated at

Rs.24.1 billion and this does not include the in-house development of software

industry has shown a CAGR of 48.9% which has been steadily improving in

the last few years.

The growth rate was 44.13% in the year 1996-97. The domestic software

industry is expected to gross Rs.36 billion in 1997-98. With the amendments

to the copyright Act and its rigorous enforcement, it is expected that

in the coming years, piracy would be brought under further control. Also,

the government has announced zero import duty on software. With the copyright

amendments and zero import duty, the domestic market is expected to show

high growth rates in the range of 40-50 percent in the coming years.

Figure 1.1: Growth of the Domestic Software Industry

1.4 Software Export Industry

The Indian software export industry continues to show impressive growth

rates. In terms of Indian rupees, the CAGR has been as high as 55.04%.

The industry exported software worth Rs.30 billion in 1985 and within a

few years, the turnover has grown multifold. In 1996-97, a total export

of US $ 1085 million (Rs.39 billion) was achieved and it is expected to

be worth US $ 1.8 billion in the current year (1997-98).

Interestingly, most of the export is in the form of providing software

services, that is developing or helping develop software for organisations

overseas. Most of domestic turnover comes through selling of software products

developed primarily in other countries. That is, the overseas revenue is

earned by providing services while the domestic revenue comes mostly through

trading.

Figure 1.2: Growth of Software Exports from India

The Indian software industry has generated an estimated software export

revenue of Rs 3,074 crore (US $853.89 million) in the first half of fiscal

1997-98. The industry has marked a record growth of 64.4 percent over the

previous year’s Rs 1,870 crore (US $519.44 million) during the

same period.

The software industry in Indian expects to reach an export level of

US $ 4.0 billion by 2000 AD For achieving this velocity of business, the

industry needs further liberalisation of the Indian economy, simplification

of procedures, deployment of additional resources for technical manpower

development, new marketing channels and providing state-of-the-art infrastructure

for software development.

Figure 1.3: Percentage Growth of Software Exports from India

1.5 Structure of Software Exports

There has been a shift towards offshore services in the software export

cargo of India. The bulk of Indian software exports have been in the form

of professional services. A detailed analysis indicates that majority of

software exports are in the areas classified as "customized" or "professional

consultancy". However, since last two years, there has been a visible shift

towards off shore project development, which also includes offshore package

development has increased to over 41% during the year. Reasons attributed

for this growth are increasing number of Software Technology Parks, liberalised

economic policy and unnatural visa restrictions by U.S. and some Western

European countries

The degree of on-site development is still very high, with as much as

59% of the work being done at the client's site, but it is expected to

decrease further in the coming years with improved data communication links.

In 1988, the percentage of on-site development was almost as high as 90%.

|

Type of Services

|

RS. Million

|

Percentage

|

|

On-Site Services

|

22890.00

|

58.7%

|

|

Offshore Services

|

11780.00

|

30.2%

|

|

Offshore Packages

|

4330.00

|

11.1%

|

|

Total

|

39000.00

|

100 %

|

Table 1.2: Structure of Software Exports

A break-up of the software activity is shown in the table below:

|

Software Activity

|

Domestic Software

|

|

Software Export

|

|

| |

Rs. Million

|

% of Total

|

RS. Million

|

% of Total

|

|

Turnkey

|

9855

|

40.9%

|

-

|

-

|

|

Professional Services

|

-

|

-

|

18213

|

46.7%

|

|

Products & Packages

|

11270

|

46.8%

|

4330

|

11.1%

|

|

Consultancy & Training

|

1675

|

6.9%

|

10685

|

27.4%

|

|

Data Processing

|

1250

|

5.2%

|

4290

|

11%

|

|

Others

|

50

|

0.2%

|

1482

|

3.8%

|

|

Total

|

24100

|

100%

|

39000

|

100%

|

Table 1.3: Break up of the Software Activity

An analysis of break-up of software activity of both domestic as well

as export industry demonstrates that Products & Packages tops the list

with a share of 46.8% in domestic market, whereas professional services

command a share of almost 46.7% in the export market.

1.6 Destination of Indian Software Exports

In 1996-97, India exported almost 58% of its total software exports of

USA and 21% to Europe. The six OECD countries (USA, Japan, UK, Germany,

France and Italy) together have 73% of the market share of the world-wide

software market. Interestingly, India's exports to these countries are

also almost 83% of its total software exports.

In the coming years, India is expected to strike many joint ventures

and strategic alliances in Europe. The trade with European nations is growing

rapidly. There have been alliances to create more co-operation between

Indian and European software companies.

NASSCOM under the aegis of Ministry of Commerce, Government of India

had initiated a Project called NASSCOM's India-Europe Software Alliance

(NIESA). The NIESA Phase-I was partly funded under the ECIP Facility 1

Scheme of the Commission of the European Communities. After successful

completion of phase I of the Project, Nasscom has now launched phase II.

This is expected to further help in increasing software exports to Europe.

Over the next two years, software exports to many Asian countries and

Australia are also expected to increase. The new markets include Korea,

South Africa, Latin America and some countries in Asia-Pacific. USA continues

to be India's largest export market. However, if the visa situation for

the US market does not improve, the export growth for the US market can

be adversely affected.

1.7 Development focus of the Software Exporters

Nearly two thirds of the companies are engaged in developing end-user application

products and services ranging from straightforward accounting systems to

specialised niche market products or customised services. The rest obtain

their revenues from consultancy, systems integration, supply of specialised

software systems, such as software tools, communications software and software

for dedicated hardware devices.

Figure 1.4: Development Focus of Indian Software Exports

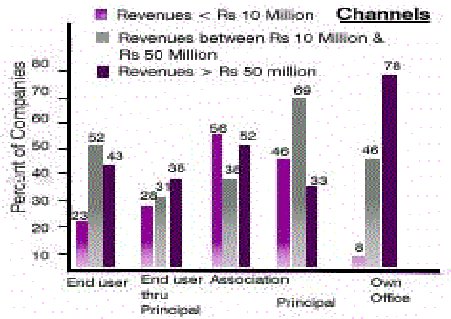

1.8 Marketing channels used by software companies

Marketing is the most critical issue for the development of the Indian

software Industry. The size of the Indian software export industry is very

small compared to the world market. To emerge as a major player in the

world software market, there has to be a significant expenditure on marketing.

In India, the software vendors operating in the export market have traditionally

depended upon direct marketing to end-users. However lately, many software

companies have set up their own offices in various countries.

Figure 1.5: A break-up of the Marketing Channels used by Indian

Software Companies

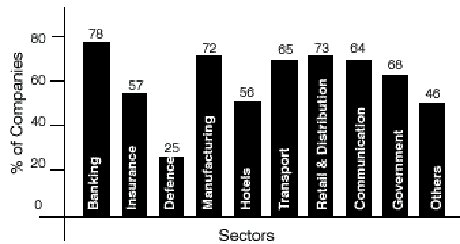

1.9 Segments of Application Software Development

Indian software companies mainly concentrate on developing application

software for three main sectors. They include

-

Banking

-

Manufacturing

-

Insurance and Other Financial Services

A segment wise break up of the software industry's revenue demonstrated

the following statistics:

Figure 1.6: A break-up of the Revenues by Sector

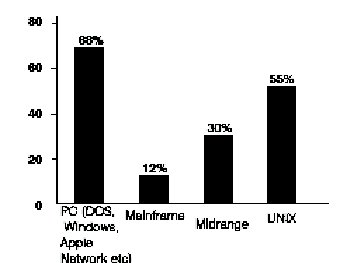

1.10 Development Platform

Majority of companies concentrate on four major development platforms -

PC (DOS, Windows, Apple), Mainframe, UNIX and Midrange. Also, as most companies

develop on more than one platform, therefore the values shown total more

than 100%. The most common combinations are Unix with PC, and Unix with

Midrange.

Figure 1.7: A break-up of the development Platforms used

1.11 Top twenty Software exporters

There are currently more than 550 companies in India which are engaged

in the business of software exports. In 1996-97, more than 52 companies

have exported more than RS 100 million worth of software. In 1991-92, only

five companies and exported software more than RS 100 million. Also in

1996-97, 17 companies exported more than RS 500 million worth of software.

This indicates the high proliferation and all-around growth of software

exports. The top twenty software exporters (in order of revenue) accounted

for almost 60% of the total software exports. The following table lists

the Top 20 software exporters by revenue.

|

Rank

|

Company

|

Exports 1996-97 in Rs Million

|

|

01

|

Tata Consultancy Services

|

6068.80

|

|

02

|

Wipro Ltd.

|

2588.40

|

|

03

|

NIIT Limited

|

1612.50

|

|

04

|

Pentafour Software & Exports Ltd.

|

1594.26

|

|

05

|

Infosys Technologies Ltd

|

1267.10

|

|

06

|

Tata Infotech Limited

|

1060.00

|

|

07

|

Satyam Computer Services Limited

|

891.80

|

|

08

|

International Computers (India) Limited

|

850.20

|

|

09

|

Patni Computer Systems Pvt. Ltd.

|

848.90

|

|

10

|

DSQ Software Limited

|

803.99

|

|

11

|

Mahindra British Telecom Limited

|

799.62

|

|

12

|

Silverline Industries Limited

|

720.22

|

|

13

|

Tata IBM Limited

|

648.80

|

|

14

|

CMC Limited

|

620.94

|

|

15

|

Mastek Limited

|

578.80

|

|

16

|

Siemens Information Systems Limited

|

554.10

|

|

17

|

L&T Information Technology Limited

|

499.30

|

|

18

|

Info. Management Resources(I) Ltd.

|

497.74

|

|

19

|

Hexaware InfoSystems Limited

|

483.50

|

|

20

|

Citicorp Info. Technology Industries

|

470.00

|

Table 1.4: Top 20 Indian Software Exporters

2 CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIAN SOFTWARE

EXPORTS

2.1 Uneven Output: Services not Packages

Indian software exports have been dominated by export of software services,

in the form of custom software work, rather than export of software products,

in the form of packages. This helps explain the recent rise in growth rates.

This rise has partly taken place because of the explosion of services work

on the 'Year 2000 problem'; now estimated to make up nearly 40% of current

software export work from India. By contrast, at the very most, just under

5% of exports came from packages in 1997/98.

One reason why packages not taken off despite India's low labour cost

advantages is because of high entry barriers despite the low cost at which

Indian companies can develop such packages.

These entry barriers are lack of familiarity with the foreign package

markets they seek to penetrate, and their distance from those markets makes

it hard to keep up with changing needs and standards. Moreover, the Indian

domestic market is a poor guide for software developers because of differences

in user needs, in work, in hardware environments, and a generally low level

of innovation.

Other entry barriers in the software package markets is high costs in

advertising and marketing effort needed to catch the attention of potential

customers. Software multinationals can spend 40-50% of annual revenue on

package sales and marketing, and 10-15% on research and development for

packages (Economist 1994). For a single large firm, this can represent

billions of US dollars-worth of investment: more than the entire output

of all Indian software producers.

Due to India's lack of reputation as a software package source and its

lack of any software brand names in a relatively brand-loyal market, high

sales would not be expected, making the unit cost of marketing and distribution

even higher. Providing

support, maintenance and upgrades for a product in a foreign market

is also either difficult or very costly.

Lastly, all this assumes success with the product, yet experience suggests

that only about 1-5% of software packages succeed, in which case huge investments

are required, which are not readily available within India. Even if available,

neither government policy nor managerial attitudes have generally encouraged

the high-risk, long-term investments necessary.

Because of these constraints, some Indian companies have agreed to undertake

custom software work at cut price for a foreign client on the understanding

that they will subsequently try to market the developed system as a package

for a niche market.

Firms and official surveys frequently classify this as 'package exports'

but such 'packages' - sometimes more accurately identified as 'semi-packaged

software' - often end up being used merely as marketing or development

platforms for further

customisation.

The alternative option for Indian exporters seeking to work on packages

is to collaborate with a foreign firm which will supply the package specifications,

marketing, support and finance. The drawback is that the Indian company

ends up just supplying programming services in return for a very small

share of any revenue. Nor will its reputation be much-enhanced for, as

with original equipment manufacturing in other fields, the product will

emerge under the foreign firm's brand name.

2.2 Uneven Export Destination: US Domination

Indian companies have exported software to more than forty countries but

there is a heavy reliance on the US market as the figure below indicates.

Figure 2.1: Destination of Indian Software Exports

The US market dominates Indian software exports partly because it is

by far the world's largest software market, constituting around half of

all software sales in the 1990s. The US has also had more liberal immigration

rules for work or residence than most other developed countries which encourages

export of onsite projects.

The US-orientation of exports might present a limitation to future growth

because US share of the world market is slowly declining. However, the

American market is still expanding substantially in absolute terms plus,

since the early 1990s, Indian software exports have shown their ability

to grow in other markets, such as those of Asia and Europe.

2.3 Uneven Divisions of Labour: 'Body Shopping Prison'

2.3.1 Uneven Locational Divisions: Onsite and Offshore

Work

Much of India's export work developing custom software is actually carried

out at the client's site overseas ('onsite') rather than offshore in India.

Back in 1988, an average of 65% of export contracts were carried out wholly

at the client site, while 35% contained some offshore elements (Heeks 1991).

This translated into just under 75% of Indian software export development

taking place overseas and only 25% in India. This was even true of work

in India's export processing zones,which were intended to be bases for

offshore work.

Subsequent surveys have shown that the amount of work carried out offshore

has increased within individual firms.

2.3.2 Uneven Skill Divisions: Dominance of Programming

During the period 1988-1998, at least 65% of export contracts were solely

for programming work billed on a 'time and materials' basis, with programming

figuring strongly in the remaining one-third of contracts. So, in general

terms, India's software export trade has been characterised by an international

skill division of labour such

that the majority of software contracts allocate only the less-skilled

coding and testing stages to Indian workers. That is to say, Indian workers

have far more often been used as programmers, working to requirements and

design specifications set by foreign software developers, rather than as

systems analysts or designers.In the Indian context, the combination of

onsite and programming work has come to be known as 'body shopping'. Amongst

other things, this has helped to reinforce a further gender division of

labour.

2.3.3 Persistence of Onsite Programming Services

Reasons for onsite programming services are as follows:

-

Trust and Risk: According to interviewees, there is a lack of trust and

a perception of risk among clients, who are uncertain of the skills, capabilities

and credibility of potential Indian sub-contractors. In order to reduce

the risk, many clients choose to retain as much control as they can over

production, only contracting out the relatively unproblematic tasks of

coding and testing, and having the work carried out onsite. Work will only

be allowed offshore if there are fairly tight, formalised specifications,

but exporters are caught in the bind that such projects are then more amenable

to automated software tools.

-

Other Client Attitudes: Client attitudes perpetuate onsite work in other

ways. According to InfoTech's (1992) survey the important factors guiding

foreign firms over onsite work are cost, credentials, productivity and

quality. Indian firms working onsite tend to score quite well on these.

However, there is a different picture for offshore or turnkey assignments.

In these cases, cost is less important while management skills, quality,

proven expertise and access to technology all become much more important.

Indian firms working offshore tend to score much less well on these, making

a transition that much less likely to occur from onsite programming to

offshore turnkey assignments.

-

Project Size: Project size affects the division of labour since small contracts

are not worth sending overseas. Nicholas (1994), for example, recommends

a minimum project size of US$100,000 before it becomes worth the time,

effort and risk to consider sending work offshore.

-

Need for Interaction: Continuous client-developer interaction is an essential

part of software development. Despite good communications links, interaction

sometimes needs to be face-to-face, which means the developers going to

the client rather than vice versa. Thus, even with offshore turnkey contracts,

the requirements analysis, preliminary design, installation and implementation

generally need to be done onsite.

-

Uneven Skills Profile: The average software development project requires

less than half the labour input to come from programmers. Yet 85% of workers

in Indian software exports are programmers. This 'programmer heavy' skills

profile, reinforced by losses of experienced staff to the overseas 'brain

drain', encourages programming-only contracts. This and constraints on

the availability of IT and project management resources within India also

reduce offshore productivity and quality in some companies, making onsite

work more attractive.

-

Indian Managerial Perceptions: Apart from the external 'push' factors noted

above, there is an internal 'pull' in favour of onsite programming because

managers perceive it to bring benefits. It produces quick revenue for low

investment, which suits the lack of risk-taking favoured by many Indian

business managers, particularly given uncertainties that exist about policy

and about the global and Indian economies. It helps by exposing staff to

foreign market trends, skills and standards. Many Indian staff also want

to work overseas and, if denied the opportunity by one company, will simply

join another which will send them abroad. This motivates most companies

to retain a measure of onsite work.

2.4 Uneven Market Share: Economic Concentration of Production

Production of Indian software exports is a heavily concentrated. By 1998,

there were about 400-500 software export firms. Most, however, are single-contract

firms employing just a handful of staff. By contrast, the top five firms

were responsible for more than 40% of all exports, and the top twenty for

70% (Dataquest 1998).

Large firms have dominated software exports thanks to the economies

of scale and entry barriers that exist in software production. Economies

of scale and barriers include those of hardware, of staff training, of

marketing and, less tangibly, of credibility and reputation.

Since Indian software exports are services rather than goods, examples

cannot easily be displayed to potential buyers to establish credibility.

There is therefore a heavy reliance on reputation, track record, references

and the skills and appearance of

the marketing team, which all go together to determine the Indian firm's

credibility. All these credibility-related factors, which principally hinge

on track record and spending on marketing, obviously work to the advantage

of larger, longer-established

firms.

The only short cut occurs if a new firm is set up by an ex-member of

one of the large IT companies. In this case the individual can make use

of his or her personal contacts and credibility. However, this does not

enable the firms to overcome technology, skills and finance barriers. This

explains their initial reliance on onsite programming services, for which

there are few scale economies, and the fact that few of them have made

significant long-term headway in software exports.

There are also biases against small and start-up companies in terms

of obtaining foreign collaborations and technology, and in dealing with

the bureaucracy. For example, despite the falling real prices of powerful

computers and telecommunications, these technologies remain beyond the

reach of many small Indian firms. Similarly, access to government support

tends to be the preserve of the larger firms.

2.5 Uneven Siting: Locational Concentration of Production

Software companies are not distributed evenly throughout India, but are

mainly located around a few major Indian cities, especially around Bangalore.

Table 3 indicates the location of company headquarters for over 550 software

companies

(including a number focused on the domestic market).

|

City

|

No. of software firms

|

|

Bangalore

|

152

|

|

Mumbai

|

122

|

|

Madras

|

93

|

|

New delhi

|

86

|

|

Hyderabad

|

34

|

|

Calcutta

|

27

|

|

Pune

|

22

|

|

Other

|

22

|

|

Total

|

558

|

Table 2.1: Location of Indian Software Company Headquarters

Haug's (1991) work has shown that five main factors play a part in the

locational decisions of new software companies. One of these - proximity

to customers - is of limited relevance in the context of software exports.

Three other factors, however, are found to have guided locational decisions

in India:

-

Labour Availability: Bangalore was seen to have abundant labour that could

be drawn from its long-standing research laboratories, educational institutes

and public sector electronics firms. Key institutions included Bharat Electricals

Ltd, the Indian Institute of Management and the Indian Institute of Science.

These have been a key source of both software employees and - in later

years - entrepreneurs.

-

Quality of Life: Bangalore benefited from its reputation for a good climate

and social life. IT workers were rapidly integrated into the city's social

fabric By contrast Mumbai

3 ANALYSIS OF OTHER SOFTWARE EXPORTING

COUNTRIES

3.1 Australia

Australian exports of products and services are worth over $2.1 billion

which shows an increase of more than 10% over last year. Professional Services

was the area that generated the greatest revenue (34%). The areas of greatest

growth in the last 12 months, were Telecommunications Products (an increase

of 83%) and Software (an increase of 79%).

IBM Australia was the highest ranked IT&T exporter (29% of the total

exports) with export revenue of $601m in the financial year 1996-97.

|

Organizations

|

Turnover

|

|

NEC Australia

|

$66.6m

|

|

CSC Australia

|

$58.3m

|

|

Mincom

|

$57m

|

|

Fujitsu Australia

|

$54.4m

|

|

Unisys Australia

|

$49.8m

|

|

Canon Australia

|

$41.15m

|

Table 3.1: The other top exporting organisations in Australia

3.1.1 Effect of East Asian Crisis in Software exports

of Australia

84% of companies active in the region reported suffering adverse affects

from the current crisis. However, devaluation of the Australian dollar

has resulted in increased price competitiveness for some Australian products

that compete with products from other markets, moreover the crisis has

assisted as customers are now looking for added efficiencies to save costs

by importing software solutions.

Malaysia was the most important market for Australia. The next most

important markets are Indonesia, Singapore and Korea, Hong Kong and Thailand.

Many organisations have changed their strategies as a result of the economic

situation in Asia. The main changes can be summarised as follows:

-

Downsized operations or reduced staff numbers in Asian operations

-

Cut in marketing activities/expenditure or stopped activities in

Asia completely

-

Changed marketing approach like less use of direct marketing and

more use of partnerships

-

Reduce margins to retain customers/distributors

-

Change of product mix (lower priced products) or marketing message

(emphasis on cost benefits)

-

Cancelled expansion plans in Asia, concentrating on maintaining existing

business

-

Organisation are changing their emphasis back on the Australian domestic

market, or focussing on other markets, primarily North America and Europe.

3.1.2 Implications for India

The above analysis shows that Australian exports will be targeted more

towards the North American and European nations and India can face stiff

competition especially after the South East Asian crisis.

3.2 Ireland

The software industry is firmly established in Ireland. The domestic sector

has innovated a broad rang of products business applications, software

tools, advanced telecommunications multimedia systems. In tandem with the

development of the indigenous sector, an equally strong overseas sector

has chosen Ireland as an offshore software location. Internationally, Ireland

is now recognised as a prime source of high quality software development

services and as the ideal gateway to European markets.

Figure 3.1: A Profile of Software Exports of Ireland

The reasons behind this booming development include: the availability of

a workforce, which is predominantly young, skilled and well educated, with

strong technological and business skills; a highly efficient and cost-effective,

world-wide communications infrastructure using state-of -the-art technology.

The software sector currently comprises more than 550 companies, 80%

of which are Irish owned. Some are small, specialised firms operating at

the forefront of software development technologies; others are larger organisations

that have successfully targeted niche markets on a worldwide basis and

have established offices overseas.

3.2.1 Focus on Exports

Ireland's small domestic market means that substantial growth is often

only attainable by servicing the needs of international markets. From the

outset, Irish software companies, anxious to exploit overseas markets,

develop a unique international orientation that is reflected in the quality

and functionality of their products. As a consequence, more than 80% of

all indigenous developers are active in overseas markets.

Figure 3.2: A Profile of Irish Software Exports

Annual output from the sector in 1995 was estimated to be worth just under

$5 Billion, almost all of which was exported. Indeed, today over 40% of

all PC packaged software (including 60% of business application software)

sold in Europe is produced in Ireland.

Ireland's indigenous software developers have a uniquely international

focus and a strong product bias, setting it apart from many other European

countries, where services account for a large proportion of software activity.

More than two thirds of Irish companies are involved in developing and/or

marketing software products.

Figure 3.3: A Comparison of Irish Export and Indigenous Software

Industry

After the U.S., Ireland exports more software than any other country

in the world, not on a per capita basis, but in absolute terms! The major

destinations for Irish software exports are given below:

Figure 3.4: Destination of Irish Software Exports

Revenue [IR£ million]

| |

1991

|

1993

|

1995

|

|

Indigenous Companies

|

291

|

336

|

390

|

|

Overseas Companies

|

74

|

81

|

93

|

|

Total

|

365

|

417

|

483

|

Table 3.2: Revenues of Irish Software Industry

|

1991 |

1993 |

1995 |

| Indigenous Companies |

41% |

49% |

58% |

| Overseas Companies |

98% |

98% |

99% |

Table 3.3: Exports (As a % of total revenue)

Figure 3.5: Composition of Irish IT Industry:

3.2.2 People with skills

The key to Ireland's success in the software business has been the continued

availability of young, well-educated people. Ireland has a unique demographic

profile - 50% under 28 years of age. A United Nations study shows that

by the year 2000, 40% of Ireland's population will be under 25 years of

age, significantly ahead of all other countries in Europe. Unlike many

countries therefore, Ireland is in a strong position to respond to the

growing shortage of IT skills around the world, and is doing so aggressively.

As enthusiastic Europeans, the Irish have a strong work ethic. This

is reflected in the rate of employee turnover, which is well below the

European average. It means that companies enjoy greater commitment from

their staff, and benefit from a higher proportion of experienced personnel

and lower annual training costs. Surveys from organisations such as the

London consultancy William M. Mercer show that foreign investors in Ireland

consider the quality and the 'can do' flexible attitude of Irish people

to be two of the country's greatest advantages.

Ireland is committed to further developing the software industry and

continues to take steps to ensure that the availability of graduates coming

through the country's 20+ universities and third level colleges is sufficient

to meet the demands of the sector. Close co-operation between industry

and academia has resulted in the provision of additional resources and

places for computing courses and also in the establishment a number of

new software-related courses - with a greater emphasis on the linguistic

skills of graduates and the newer software and telecommunications technologies.

The education system is highly-rated - a recent report by the International

Institute for Management Development ranked it the best in Europe - and

is ideally geared to producing skilled employees for the software sector.

3.2.3 Focus for Investment

Public investment in software development companies over an extended period

of time has been largely indirect, but highly significant in making this

one of the fastest growing sectors of the economy. Tax incentives, and

grants for employment, capital investment, training and research and development

have contributed to attracting over 100 foreign companies to set up operations

in this sector which achieve annual revenue growth in of over 25%.

3.2.4 Technology in place

The services provided by both Irish and international companies operating

in this area include translation and localisation, disk and CD ROM manufacturing,

mastering and duplication, user manual printing, packaging, turnkey and

fulfilment services and technical support.

Ireland's digital telecommunications system is one of the most advanced

in the world and enables software developers to link across the world for

real-time development activities, and provides for pan-European and world-wide

customer support.

The transformation of the telecommunications infrastructure has come

about as a result of the investment of $5 Billion by Telecom Ireland in

the development of fully integrated digital network. Over 75% of all customers

are now connected to digital exchanges, which in turn are interconnected

by digital transmission systems.

3.3 Finland

The growth rate of the finnish software industry has been 60% in 1997 The

level of software export is still low, only FIM 500 million in 1997. It

is about four per cent of the total IT revenue in Finland.

There are about 420 software companies in Finland out of which most

of them are local service companies and do not have software products for

international markets. The revenue of software product business was FIM

3.5 billion in 1997.

4 INDIAN SOFTWARE EXPORTS - EVOLUTION

& STATE POLICIES

In this section, we shall try to provide explanations for the spectacular

growth in India's software exports and rapid changes in the use of IT by

focusing on the role of changes in governmental policies. We shall also

try to examine the problems and opportunities that software posed for the

policy makers in the Indian state and what are the implications of the

emphasis on software exports towards the integration of India's economy

with world trade and investment patterns. Also the recognition of software

as the major growth sector for earning foreign exchange in the IT Taskforce

recommendations assume significant importance over here and we shall examine

them in great detail.

4.1 Introduction

The term liberalisation is used to encapsulate the significant shifts in

India's economic policies, shifts that have occurred on a number of fronts.

The government has by altering its policies regarding trade in computer

equipment, software, and FDI in information and communication activities,

removed blockages to growth in the use of information technology.

Consistent with the protectionist views towards industry, India's software

policies before 1984 were consistent with a model of state-led planned

development. In the mid 1980s, a guided and guarded economic liberalisation

took place that emphasised both greater access to imports and the promotion

of software exports while still closely regulating the domestic computer

and software industries. However, it became clearer in 1991 with the state

slowly getting out of the way. In fact in India, economic liberalisation

was combined with policies to encourage and direct the introduction, adoption,

and use of information technologies and to advance national capabilities.

Of particular importance in this regard are the evolution of policies:

-

to promote the software industry and software exports through deputation

contracts,

-

to enhance information resources and human skills relevant to information

technologies,

-

to shift the composition of software exports, and

-

to capture a higher value added segment of the global software industry.

The BJP Governments latest initiative in setting up the IT Taskforce and

for the first time in India's history trying to get suggestions from the

general public (using the web-site http://www.it-taskforce.com) shows governments

long-term commitment towards the growth and development of this industry

by following the policy of liberalisation.

4.2 A brief history in time - Software Policy prior to

1984

Over the past 45 years, Indian political and technical think tanks sought

to achieve economic growth, modernisation, and industrialisation through

state direction of investment and the substitution of nationally produced

products and services for actual and potential imports. The Planning Commission

identified priority areas for public and private investment in five-year

development plans. Although the electronics and computer sectors were not

emphasised as much as the role of manufacturing in Indian development plans,

these areas were increasingly discussed beginning in the late 1960s and

early 1970s. Following the recommendations of Bhaba Committee, the Electronics

Commission and the Department of Electronics (DoE) were instituted in 1970.

These became the primary agencies for the development of India's IT strategy.

The framework for software exports, which has been operational since

the early 1970s, allowed the import of computers by those wishing to export

software above 200% of the value of the imported computer over a period

of 5 years. In 1976, the government allowed NRIs to invest in Indian software

operations. If they were using foreign capital, a software export commitment

of 100% of the computer's values over a period of 5 years was to be made.

In 1981, a revision of the software export policy was announced that

further accentuated the emphasis on national self-reliance. Imports of

computers were allowed only with proof of guaranteed exports in place.

Performance and progress reports to the DoE were required every 6 months,

and legal bonds were required to cover the eventuality that the schedule

of export obligations was not met over the five-year period. In retrospect,

one might consider that the high export requirements for imported computers

might have contributed towards the "export of human resources" as a strategy

to expand software exports. This essentially involved lower requirements

for imports of equipment to build industry capital and infrastructure domestically

in India.

4.3 1984-1990: Guided and Guarded Liberalisation

The term sea change is widely used to describe the significant policy shift

that began to occur in discussions leading up to the computer policy of

November 1984. Only one month after Mr. Rajiv Gandhi became the Prime Minister,

the computer policy resolved a number of ongoing debates. The new policy

was prompted by a number of emerging conditions in global computer services

markets. The growing world demand for data processing and software services

was seen to present the opportunity for Indian companies to sell computer

software and services abroad. According to some, India could leapfrog the

industrial age, going from being an underdeveloped agrarian economy directly

to becoming an information economy in an information revolution.

The 1986 software policy had the objectives of radically expanding Indian

software exports and of changing the composition of software exports. It

had the following objectives:

-

to promote software exports to take a quantum jump and to capture

a sizeable share in the international software market,

-

to promote the integrated development of software in the country

for domestic and export markets,

-

to sirnplify the existing procedures to enable the software industry

to grow at a faster pace,

-

to establish a strong base for the software industry in the country,

-

to promote the use of computers for decision making, and

-

to increase work efficiency.

The measures designed to facilitate the achievement of these objectives

included:

-

Liberalisation of access to imported inputs required by software

firms

-

De-licensing of production capacity for computers and electronics

equipment.

-

A shift from the state-led development of the national software and

computer industry towards a greater role for the Indian private sector

-

Allowing solely owned foreign firms to operate 100% export-oriented

units within India

-

Better access to telecommunications services

-

Reduction of import tariffs and income taxes

-

Assistance in the training and education of computer software personnel.

-

A shift towards a national focus for tighter integration with international

computer service corporations and global services markets.

A number of national agencies, programs, and policies operating in a market

context were initiated to facilitate the achievement of software export

objectives. These included:

-

Software Development Agency in the DoE,

-

A series of software technology parks that provided the telecommunication

infrastructure needed by the software companies,

-

Organisation of software export seminars by the trade Development

Authority and

-

The creation of the electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion

Council, the latter two being sponsored by the Ministry of Commerce.

By 1990, there were several major forms of software exports from India.

The overall volume of exports of software and services during 1989-1990

was estimated to be around $110 million, up from $26 million in 1985 before

the software policy was introduced. The majority of exports - around 80%

- were in the form of deputations, on-site consultancy, professional services,

or body shopping. Software and service exports also included projects consultancy

or turkey projects - wherein the overall management of the work was in

the hands of the Indian consulting firm rather than of the client - that

comprised around 15% of exports. Analysts argued that further export growth

were to be sought in the areas of software development based on clients'

specifications, Indian based software export operations, systems maintenance

and service (outside India), and training students and retraining professionals.

4.4 Industry Evaluation of Software Policy in 1990

Among the policy questions facing the Indian government were:

-

The appropriateness of the policy's objectives.

-

The importance of altering the composition of software exports.

-

The nature of liberalisation, government support or other policy

changes required in order to achieve those objectives.

4.4.1 Appropriateness of policy's objectives

A question that was rarely considered at this point was the appropriateness

of the software policy's export objectives in terms of national information

technology goals. The goal of rapidly expanding exports of software and

computer services via deputation was problematic in that the achievement

of this goal ran the risk of eroding India's strengths and of expropriating

resources away from meeting national needs and demands. Exporting software

and computer services via deputation arose as a response to the demands

abroad, the capabilities that Indians possessed, the lack of effective

access to foreign markets, and the lower availability of information technologies

in India. This helped diminish what was seen to be the Indian comparative

advantage: trained and capable people. The NASSCOM set the goal of reducing

the percentage of exports in deputation contracts from the 80- 85% in 1990

to around 50% by 1995. With a significant growth in exports, however, even

the reduced proportion would still represent a tremendous absolute expansion

in the number of people undertaking on-site work outside India.

The former head of CMC, P.D. Jain noted that to significantly expand

the software exports, some of the best people would be taken away from

the skilled work force available to the Indian computer services industry.

Robert Schware of the World Bank in an October 1989 consultation on the

world software industry in New Delhi, proposed that governmental policy

should encourage the development of a public and private national industry

as well as the development of a private sector export-oriented industry.

4.4.2 Altering the composition of Software Exports

A second policy question related to the necessity of efforts to alter the

composition of software exports. Under existing conditions, a low portion

of the value-added in the world software industry was captured by Indian

firms, whose workers might be involved in tasks such as coding or testing

software rather than in managing projects, the design of software, or the

integration of different computer and software systems. Over the long term,

Indian companies ran the risk of becoming stuck in the low technology and

low value added activities of world software production, such as writing

code or conversions of existing software programs to work with new computers

or operating systems.

In 1990, a number of steps were identified by industry representatives,

whereby Indian firms could shift the composition of software exports. These

included:

-

developing long term relationships with clients,

-

building connections with foreign affiliates,

-

developing software for hardware manufacturers prior to the release

of new equipment,

-

setting up corporate service centres in India, and

-

constructing alliances among Indian software services and other activities

such as engineering or accounting in order to develop niche specialisation's.

At that time, many difficulties were recognised in efforts to alter the

composition of exports. As a nascent industry, many Indian software firms

lacked the necessary experience in management skills. India was also geographically

remote from important world markets, making it difficult to build relations

with prospective clients. However, alongside these difficulties, there

were significant advantages in bringing work back to India for Indian based

software export operations. These advantages included the lower costs of

living and the opportunity to remain within their own culture and lower

administrative costs for contracts. Large geographic distances also allowed

for the remote use of clients' computing facilities via telecommunications

while it was night time in the West, reducing costs and expanding the use

of clients' computer resources.

4.4.3 Nature of liberalisation, government support or

other policy changes required

Several policy changes on the part of the Indian government to allow greater

access to foreign inputs such as computers, software, and training were

therefore necessary to facilitate the achievement of these goals.

The areas in which the need for policy changes was especially emphasised

were:

-

necessity of obtaining import licenses for equipment,

-

continuing tariffs on imported software under the open general license

scheme,

-

high export performance commitments to offset the foreign exchange

cost of foreign equipment, and

-

improved availability, quality, and price of inputs obtained within

India.

The development of stronger national and international protection for intelligence

for intellectual property rights was also seen as essential to the development

of the software industry. Foreign software firms that might send work to

India were hesitant to do so if they could not be sure of the protection

of their proprietary rights.

4.5 Economic Liberalisation - 1991 - 1998

Policies allowed 51% equity holdings for software companies investing in

India. That is to say, changes in the rules for foreign direct investment

drew capital to India and accelerated the growth of Indian-based software

activities. Changes in investment rules allowed more investment by foreign

software companies in production facilities in India. This created an even

greater demand for trained workers and allowed expansion into new areas

of software and computer services, such as providing Indian software design

or data service centres for the global operations of transnational corporations.

Among the US companies with software operations in India by the first half

of the decade were Texas Instruments, Motorola, Hughes, Hewlett-Packard,

IBM, Oracle, Onward Novell and Citicorp.

The overall role of the state, thus, shifted in 1991. The new measures

introduced were:

-

the virtual abolition of industrial licensing,

-

the dilution of Monopolies Act requirements that expansions or mergers

be approved,

-

the relaxation of FERA prohibitions on foreign companies holding

a majority stake in certain Indian operations,

-

the abolition of import licenses, moves towards convertibility of

the rupee, and

-

the lowering of customs duties.

Software exports were also aided by a decline in disputes over intellectual

property rights and a lessening of complaints from the international software

industry.

Crucial to the deputation strategy was the receptivity of the host country

to temporary workers and potentially permanent migrants. Deputation was

also contingent on the ability to obtain a visa quickly in order to allow

admittance for a specific worker when that worker's skills were required.

In 1992-93, for instance 36% of India's software exports were in the form

of on-site consultancy in the United States, and the US accounted for 58%

of India's overall software exports. In 1993, electrical engineers and

software workers in the US began to claim that their job openings and wage

levels were being undercut by the extensive use of temporary workers by

large software companies. The US Department of labour responded to these

concerns in December 1994, by issuing a new set of regulations for granting

visas to guest workers.

Finally the Indian software industry also benefited from the end of

the Cold war. Certain restrictions on the export of information technologies,

which had obstructed India's access to some computers and operating systems,

were removed by the US in conjunction with dissolving the Coordinating

Committee on Multilateral Exports Control (COCOM).

4.6 PM's IT Task force - The New IT Policy of the Government

The new BJP Government has recognised the importance of IT in India's exports.

They have formulated the new IT policy via the PM's IT Task force. The

IT Task Force has prepared three documents that extensively detail the

evolution and the future of the Indian IT industry and also the recognition

of the fact that communications infrastructure has to play an important

part in the development of this industry. Here we discuss excerpts from

the main policy document "Information technology Action Plan". The preamble

of the policy exemplifies the Governments commitment:

|

PREAMBLE TO IT ACTION PLAN

|

| For India, the rise of Information Technology is

an opportunity to overcome historical disabilities and once again become

the master of one's own national destiny. IT is a tool that will enable

India to achieve the goal of becoming a strong, prosperous and self-confident

nation. In doing so, IT promises to compress the time it would otherwise

take for India to advance rapidly in the march of development and occupy

a position of honor and pride in the comity of nations.

The Government of India has recognised the potential of Information

Technology for rapid and all-round national development. The National Agenda

for Governance, which is the Government's policy blueprint, has taken due

note of the Information and Communication Revolution that is sweeping the

globe. Accordingly, it has mandated the Government to take necessary policy

and programmatic initiatives that would facilitate India's emergence as

an Information Technology Superpower in the shortest possible time.

This commitment to Information and Communication Technology in the National

Agenda for Governance has been forcefully articulated by Prime Minister

Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee on a number of occasions. In his first televised

addresss to the Nation on March 25, 1998, the Prime Minister declared that

promotion of Information Technology would be one of his Government's five

top priorities. |

The main document of the policy highlights the important thrust areas.

It goes on to say the following:

"The Government of India, recognising that the impressive growth

the country has achieved since the mid-Eighties in Information Technology

is still a small proportion of the potential to achieve, has resolved to

make India a Global IT Superpower and a front-runner in the age of Information

Revolution. The Government of India considers IT as an agent of transformation

of every facet of human life which will bring about a knowledge based society

in the twenty-first century. As a first step in that direction, the following

revisions and additions are made to the existing Policy and Procedures

for removing bottlenecks and achieving such a pre-eminent status for India."

As can be seen the thrust of the government policies (current and the

future) are aimed at achieving three basic objectives:

-

to make India a Global IT Superpower

-

by being a front-runner in the age of Information Revolution and

-

transform every facet of human life to bring about a knowledge based

society in the twenty-first century

To accomplishing these basic objectives the IT policy has made recommendations

in the following areas:

-

Info-Infrastructure Drive: Accelerate the drive for setting up a

World class Info Infrastructure with an extensive spread of Fibre Optic

Networks, Satcom Networks and Wireless Networks for seamlessly interconnecting

the Local Informatics Infrastructure (LII), National Informatics Infrastructure

(NII) and the Global Informatics Infrastructure (GII) to ensure a fast

nation-wide onset of the INTERNET, EXTRANETs and INTRANETs.

-

Target ITEX - 50: With a potential 2 trillion dollar Global IT industry

by the year 2008, policy ambiance will be created for the Indian IT industry

to target for a $ 50 billion annual export of IT Software and IT Services

(including IT-enabled services) by this year, over a commensurately large

domestic IT market spread all over the country.

-

IT for all by 2008: Accelerate the rate of PC / set-top-box penetration

in the country from the 1998 level of one per 500 to one per 50 people

along with a universal access to Internet / Extranets/ Intranets by the

year 2008, with a flood of IT applications encompassing every walk of economic

and social life of the country. The existing over 600,000 Public Telephones

/ Public Call Offices (PCOs) will be transformed into public tele-info-

centres offering a variety of multimedia Information services. Towards

the goal of IT for all by 2008, policies are provided for setting the base

for a rapid spread of IT awareness among the citizens, propagation of IT

literacy, networked Government, IT-led economic development, rural penetration

of IT applications, training citizens in the use of day-to-day IT services

like tele-banking, tele-medicine, tele-education, tele-documents transfer,

tele-library, tele-info-centres, electronic commerce, Public Call Centres,

among others; and training, qualitatively and quantitatively, world class

IT professionals.

Now we shall discuss the main provisions that have been encapsulated under

the above broad areas to achieve the objectives.

4.6.1 Info Infrastructure drive

The main policy considerations relevant for software exports under this

are:

-

(7) For setting up ISP Operations by companies, there shall be no license

fee for first five years and after five years a nominal license fee of

one rupee will be charged.

-

(18) Existing Software Centres by themselves may not be able to fulfill

the high targets now set for the IT industry by the year 2008. International

experience has shown that hi-tech industries flourish essentially in the

rural hinterland adjacent to cities with modern telecom and communication

infrastructure and top class hi-tech educational/research institutions.

India will promote such 'Hi-tech Habitats' in the rural hinterland adjacent

to suitable cities. For this purpose suitable autonomous structures will

be designed and progressive regulations will be framed to facilitate infrastructurally

self-contained self-financed Hi-Tech Habitats of high quality. Initially,

five such Hi-Tech Habitats shall be planned and implemented in the rural

hinterland of the cities: Bangalore, Hyderabad, Pune, Delhi and Bhubaneswar.

It is estimated that progressively 50 such Hi-Tech Habitats can be viably

set up by empowering the State Governments to autonomously nucleate them

within a technologically progressive and administratively liberal set of

guidelines to be prepared by a special Working Group on Hi-Tech IT Habitats

to be set up by the Task Force.

The provisions no 7 and 18 essentially relate to the setting up of infrastructure

for the software industry. The provisions are important in the light of

the fact that it is for the first time that the Government has very clearly

articulated the importance of Hi-Tech centres for the development of software

industry. These hi-tech centres that would provide high quality communication

links are extremely essential for the offshore development centres that

contribute a bulk of software exports from India. Besides it it also important

to privatise the Internet Services industry (which since been started by

granting licences for the private service providers to operate) to provide

high bandwidth links to the world software markets and at a competitive

prices. What is now needed is to remove the monopoly of VSNL to provide

international gateway services and allow the private operators to operate

their own international gateways for data-transmission.

4.6.2 Target ITEX-50

For creating a congenial ambience for exporters of IT Software and IT Services

(including IT enabled services) to reach the export target of US $ 50 billion

by the year 2008, the following incentives shall be provided (these are

discussed along with the implication of each incentive in the following

pages):

-

(19)(c) IT Software shall be entitled for zero customs duty and zero

excise duty.

-

(23) IT Software and IT Services companies, being constituents of the

knowledge industry, shall be exempted from inspection by Inspectors like

those for Factory, Boiler, Excise, Labour, Pollution/Environment etc.,

These sections essentially refer to the exemptions being given to the software

exporters from the various controls and duties of the Government of India,

which would result in their faster development. Software import duties

will go that would go a long way to provide the much needed boost to the

industry. Besides exempting the industry from the control of various ministries

will reduce the gestation period of software projects by a lot of time

thereby reducing the cost of setting up such a unit.

-

(26) The Ministry of Civil Aviation shall issue the following notifications/

amendments in the regulations:

-

Export shipment time for air cargo will be reduced to less than 24 hours.

-

"Known Shipper" will be introduced to avoid delays on account of cooling

off period.

-

Cargo companies and other associated agencies to allow consolidation

of export air cargo.

This would reduce the time lag and help in meeting the essential delivery

deadlines, which is again extremely important. Currently export can take

as long as 15 days, which reduces the industry's competitiveness in delivery

of software vis-à-vis other competitors.

-

(27) Section 80 HHE of the Income Tax Act provides for income tax exemption

to profits derived from software and services exports. This section shall

be amended as follows:

-

The existing formula will be so changed that tax on profits shall

not have any relation to domestic turnover.

-

The definition of software and export turnover will be changed

so as to include IT services exports.

-

The benefits of this Section for income tax exemption to profits

from exports will be extended to supporting IT Software & IT Services

developers.

This would help a lot of companies (a large part of Indian software exports

are in IT services) to plough back their earnings to their business and

gain significant advantages by reducing the cost of capital.

-

(33) As the traditional method of asset-based funding of working capital

would not meet the adequate and timely requirements of fund of the software

sector, a differential and flexible approach shall be adopted by giving

special dispensation towards working capital requirements of this sector

in view of the unique nature of the industry. Accordingly, RBI shall issue,

by 15th August 1998, new guidelines with regard to working capital requirements

for the IT software and services sector which would be based on simple

criteria such as turnover. Banks shall be advised to give 25 percent of

the contract value for 18 months, with the first six months as term loan

(without collaterals) and from the 7th month onwards annualized Cash Flow

Statements shall be accepted instead of collaterals.

-

(34) IT software and services industry shall be treated as a Priority

Sector by banks for the next five years. This would help to meet the requirements

of IT software and services exports, and also the IT industry and applications

within the country. Major banks will be advised to create specialised IT

financing cells in important branches, where IT Software and Services units

are sufficiently large in number. Performance in this dimension will be

monitored by the Ministry of Finance.

-

(35) Against the present estimate of Rs. 400 crores of working capital

for the industry, the amount shall be increased to around Rs. 1200 crores

by the year 2000 subject to the broad criteria of pro-rata increase for

the prospective requirements 24 months ahead as compared to the actuals

of the current requirements at any given time. As quantitative targeting

is not appropriate, a system will be put in place, which would enable substantial

increase in working capital provided by the banks.

Sections 33,34 & 35 relate to the government efforts to provide working

capital funds to the industry, which is an important provision because

the industry has been plagued by working capital crisis for long which

has hindered its growth. The government's efforts are focussed in the following

directions:

-

Provide advance loans for the export contracts that have been already

gathered.

-

Put IT exports in priority sector lending scheme, which would force

banks and FIs to provide a certain percentage of their annual lending's

to this sector and at a much lower cost and also without getting credit

ratings, which is a time consuming process.

-

Increase the estimate of the Working Capital requirements of the

industry from the current Rs. 400 Crores to Rs. 1200 Crores (trebling of

the original amount).

-

(37) The banks shall be allowed to invest in the form of equity in dedicated

venture capital funds meant for IT industry as part of the 5 percent of

increment in deposits currently allowed for shares.

-

(38) Banks/FIs like ICICI, IDBI, UTI and SBI shall set up joint ventures

with Indian or foreign companies for setting up of at least four different

venture capital dedicated funds of a corpus of not less than Rs. 50 crores

each to cater to the credit need of the industry. Such venture capitalists

may be allowed to set off losses in one invested company and profit in

another invested company during the block of years for the purpose of income

tax

In the above provisions the government has finally realised that the success

of IT industry is dependent on Venture Capital financing, which has been

the driving force for the success of IT companies in US. This move would

give a fillip to the growth of the industry and also through the return

of many Indian run Californian software companies who have highlighted

the absence of venture capital to be the main reason for their reluctance

to invest in India.

-

(41) Dollar Linked Stock Options to employees of Indian Software companies

were announced in the 1998 Budget and detailed guidelines on this have

been issued by DEA, Ministry of Finance. This shall be modified in accordance

with the definition of IT Software and IT Services given under (19)(a)

and (b) above.

-

Employee Stock option schemes for stock listed in India would also be

encouraged. Also, clarification shall be issued that income tax is applicable

only at the time of sale and not at the time of excise of option.

For a software industry the only tangible assets are its people and as

such they must be highly rewarded to produce the levels of motivations

that are needed to enhance productivity. This move recognises the importance

of newer means to reward the employees in the organisation's performance

by making them an owner in the firm. Also since the software industry is

a global industry ownership of stocks listed in exchanges outside India

is equally important.

-

(42) Recognising the high velocity of business, high degree of competition

and fast technological obsolescence faced by the IT software and IT service

exporters, RBI shall be maximally accommodate the following:

-

(a) A blanket approval for overseas investment for acquisition

of software/IT companies across the board for software exporters with previous

three years cumulative actual export realisation in excess of US $ 25 million

to be given up to 50 % or US $ 25 million, whichever is lower, out of the

cumulative actual export earning of the previous three years. This is subject

to submission of a certificate of software industry by appropriate authorities.

-

(47) On-site IT Services should be made easier by combating Visa regulations

of the recipient countries through a planned diplomatic strategy by the

Ministry of External Affairs and the Indian Missions abroad for which MEA

will create a suitable dedicated structure. This will also include signing

of totalisation agreements, wherever necessary so as to maintain the competitive

advantage of Indian companies.

-

(48) Returns from package software development shall be increased by

enabling Indian Marketing companies to set up wholesale companies abroad.

They shall also be given maximum flexibility in organising the marketing

of package software from India through INTERNET.

The above provisions are a removal of the most important bottleneck in

the growth of the software export industry. The government has for the

first time recognised that the software export industry is essentially

a global industry and so useless restrictions on acquisition of development

and marketing subsidiaries abroad should not be prevented. Besides Visa

problems are the core issues for on-site consultancy by Indian companies